Criminal Forensic Psychiatry

Forensic Neuropsychiatry in Criminal Litigation

Dr. Datta has served as a court appointed expert and worked with attorneys in state and federal courts, providing his expertise on a range of psycho-legal matters. He has also published and presented on such topics in peer reviewed journals and national conferences.

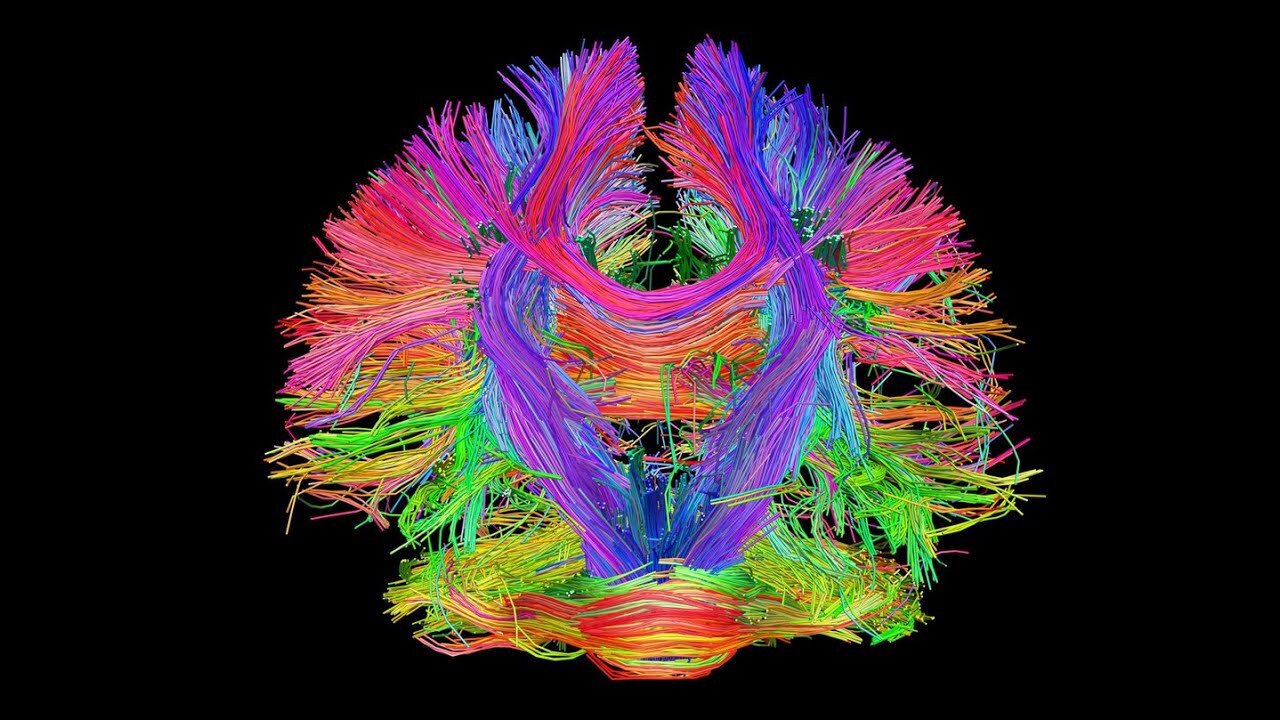

As a neuropsychiatrist, Dr. Datta has particular expertise evaluated defendants with neuropsychiatric disorders such as Traumatic Brain Injury, Dementia, and psychiatric manifestations of neurological disease (e.g. stroke, epilepsy, movement disorders, COVID-19, tumors, autoimmune encephalitis). He has evaluated individuals with charges ranging from trespassing to sex offenses and multiple murders.

Criminal Competencies

Competency to Stand Trial

Evaluating competency to stand trial is one of the most frequent types of forensic evaluation in criminal courts. It is considered a cornerstone of a fair judicial system to determine a defendant's competency to stand trial. The rationale behind this is that it is unfair to subject someone to the stress and ordeal of a trial or allow them to proceed through the criminal justice system if they lack the cognitive capacity to understand the charges against them or effectively defend themselves.

In Dusky v. United States (1960), the US Supreme Court established the three basic prongs required for competency to stand trial: (1) factual understanding of the proceedings; (2) rational understanding of the proceedings; and (3) rational ability to consult with counsel.

An evaluation of competency to stand trial includes an evaluation of the mental state of the defendant, a structured interview to assess their competency to stand trial, a review of their prior medical and psychiatric history, social and developmental history, a review of any relevant discovery and prior medical/psychiatric records. Dr. Datta uses the Evaluation of Competency to Stand Trial-Revised (ECST-R), a semi-structured interview tool developed and validated to assess criminal defendants’ capacities as they relate to courtroom proceedings that is based on the prongs of the Dusky standard.

Common disorders that can impair competency to stand trial include schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, severe depression, dementia/neurocognitive disorders, and intellectual disability. The physiological effects of medications and drugs can also affect competency, as can other medical conditions.

In addition to determining competency to stand trial, evaluations of this kind may also include an evaluation of whether the person's competency can be restored. In particular, courts may ask whether involuntary use of antipsychotic drugs is indicated to restore a defendant's competency.

Competency to Waive Miranda Rights

Another less common criminal competency evaluation is the competency to waive one's Miranda rights. In Miranda v Arizona (1960) the US Supreme Court held that the Fifth Amendment right to not self-incriminate oneself applies outside of criminal court proceedings, and an individual:

“must be warned prior to any questioning that he has the right to remain silent, that anything he says can be used against him in a court of law, that he has the right to the presence of an attorney, and that if he cannot afford an attorney one will be appointed for him prior to any questioning if he so desires.”

Any such waiver must be knowing, intelligent, and voluntary. If a defendant made incriminating statements, these are not admissible if they do not meet these criteria. Mental disorders including delirium, dementia, psychosis, substance intoxication and so on, may impair an individual's ability to waive their Miranda rights. Unlike competency to stand trial, this evaluation requires the forensic evaluator to retrospectively assess the individual's competency at the time they waived their rights.

The AAPL Guidelines on Forensic Psychiatric Evaluation of Competency to Stand Trial provide further detail on this topic.

Dr. Datta co-authored a paper on Neurobiological Evidence and Criminal Competencies that was published in Behavioral Sciences & The Law.

Criminal Responsibility

The insanity defense allows individuals, under certain circumstances, to be found not criminally responsible for their actions. The tests of insanity vary, and different jurisdictions have different criteria for what constitutes legal insanity. Historically, one of the earliest modern tests of insanity was the "wild beast" test, which held that an insane person was someone so deprived of their understanding or memory that they could not be held responsible for their actions any more than a wild beast. However, this test is now considered outdated, and modern tests focus on a person's ability to understand the nature and consequences of their actions.

The M'Naughten rule (which has numerous spelling permutations) is the most well-known legal test of insanity. It was established following the trial of Daniel M'Naughten, who was found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to a mental asylum after he shot and killed Edward Drummond, Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel's secretary. The verdict caused a public outcry and led to a review of the insanity defense, resulting in what are now known as the M'Naughten rules. These hold that a person is presumed to be sane unless:

"at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or, if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong."

In the 1950s the American Law Institute developed its Model Penal Code which included a test of insanity that became widely adopted. The ALI standard held that:

"A person is not responsible for criminal conduct if at the time of such conduct as a result of mental disease or defect he lacks substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality [wrongfulness] of his conduct or to conform his conduct to the requirements of law."

Following the uproar surrounding John Hinckley Jr.'s acquittal as not guilty by reason on insanity for his attempted assassination of President Ronald Regan, congress passed the Insanity Defense Reform Act in 1984. This law significantly narrowed the federal test of insanity from the ALI standard to a version of the M'Naughten rule:

"It is an affirmative defense to a prosecution under any federal statute that, at the time of commission of the acts constituting the offense, the defendant, as a result of severe mental disease or defect, was unable to appreciate the nature and quality or wrongfulness of his acts. Mental disease or defect does not otherwise constitute a defense."

Common disorders that can impair criminal responsibility include schizophrenia, delusional disorder, bipolar disorder, and psychotic depression. Some forms of dementia (e.g. behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia) may also impair criminal responsibility, but it is likely that such a defendant would be found incompetent to stand trial and not restorable. Rarely, PTSD and dissociative disorders may also affect criminal responsibility.

The AAPL Guidelines on Forensic Psychiatric Evaluation of Defendants Raising the Insanity Defense provides further detail on this topic.

Dr. Datta co-authored a book chapter on Criminal Responsibility and Dementia, published in Representing People with Dementia: A Practical Guide for Criminal Defense Lawyers, edited by Elizabeth Kelley.

Sentencing Mitigation

After a defendant pleads guilty to an offense, defense attorneys may request an aid-in-sentencing evaluation from a forensic psychiatrist. Judges often have significant latitude to depart from sentencing guidelines and may consider both aggravating and mitigating factors. Increasingly, courts recognize that treating mental illness and substance use disorders can be a crucial component of rehabilitating offenders and reducing the risk of recidivism.

These evaluations typically involve a detailed diagnostic interview, collateral interviews, a review of medical and psychiatric records, a review of criminal records and relevant discovery, and psychological testing. The resulting report may contextualize the offending behavior within the individual's life story, including family history and childhood and developmental factors. If a causal link exists between the offense conduct and a mental illness or substance use disorder, the report will explain it.

These reports may also provide treatment recommendations and, where appropriate, recommend diversion from custodial sentencing to treatment. The reports may also opine of prognosis. Risk assessment tools regarding violence, sexual offending, or general recividism risk may be included.

If the offender has a disorder that may be especially adversely affected by a custodial sentence (e.g. autism spectrum disorder), the forensic report will explain this so that it can be taken into consideration.

Violence Risk Assessment

The VRAG (Violence Risk Appraisal Guidelines) is one of the most commonly used actuarial violence risk tools. Actuarial instruments use statistical methods to assess risk factors associated with violence, weighing items for the total variance they account for. Total scores are then cross-referenced to estimate recidivism risk based on groups with the same score.

The most common Structured Risk Assessment Instruments (SRAIs) used by forensic psychologists in one survey were (Viljoen et al., 2010):

-

PCL-R (Psychopathy Checklist-Revised) or PCL-SV (64.8%)

-

HCR-20 (41.8%)

-

Static-99 (32%)

-

VRAG (27.9%)

-

SVR-20 (16.4%)

-

LSI-R or LSCMI (12.3%)

-

SORAG (11.5%)

The PCL-R is a measure of psychopathy, which has been found to be strongly associated with recidivism risk in violent offenders. There are specific tools for assessing risk of sexual violence recidivism including the Static-99R, SORAG, STABLE-2007, and ACUTE-2007.

While courts continue to rely on such tools, the state of the science is far from perfect and they must be used with caution. Some of these measures, especially for sex offender recidivism, may vastly overestimate risk.

Determinations of future risk of violence has implications for release on bail, parole, capital sentencing, civil commitment, sexually violent predator commitment, and sex offender registration.

Risk assessment is different from predicting the risk of future dangerousness. The American Psychiatric Association, in their amicus brief in the case Barefoot v Estelle (1983), noted:

"The unreliability of psychiatric predictions of long-term future dangerousness is by now an established fact within the profession."

More recently, in 2000, a review of violence risk assessment in the British Journal of Psychiatry found:

"Violence risk prediction is an inexact science and as such will continue to provoke debate."

Approaches to risk assessment include clinical risk assessment, structured professional judgment, and actuarial risk assessment tools. Clinical risk assessment is the least accurate of these methods, but it can be helpful in identifying risk and protective factors and intervening in modifiable risk factors.

The HCR-20 is the most widely used example of a structured professional judgment tool. It includes 20 risk factors that are weighed based on their severity and relevance to a particular case, and used to formulate a narrative assessment of the individual's violence risk.

Malingering

Commonly malingered syndromes in forensic settings include PTSD, cognitive impairment, amnesia, and psychosis. More commonly seen than complete malingering, where the entirety of the psychiatric presentation is fabricated, is partial malingering. In partial malingering, defendants may have a psychiatric disorder but either exaggerate the severity of symptoms, falsely attribute symptoms to the legal matter at hand, or claim a past psychiatric disorder is currently active when the individual is actually in remission. Finally, not all exaggeration may occur with the deliberate intention to deceive.

Malingering must also be differentiated from factitious disorders, dissociative disorders, and functional cognitive disorders. These disorders do not involve the intentional production or reporting of symptoms with the motivation of external incentives.

DSM-5-TR defines malingering as:

"the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms, motivated by external incentives such as avoiding military duty, avoiding work, obtaining financial compensation, evading criminal prosecution, or obtaining drugs."

Malingering is a common occurrence in medico-legal settings, where individuals being evaluated may be motivated to feign or grossly exaggerate psychiatric symptoms in order to avoid prosecution or obtain financial compensation. A standard forensic psychiatric evaluation will always include an assessment of malingering. During the clinical assessment, inconsistencies and atypical presentation may indicate feigning, and psychological testing can reveal response styles that may be consistent with malingering. However, it's important to note that the assessment of malingering requires inferences about the motives underlying the individual's response styles, which is not usually revealed by psychological testing alone. Testing can reveal poor effort, whether an individual is likely to be exaggerating symptoms, or reporting symptoms atypical for known psychiatric disorders, but it cannot usually assess whether the reason for that is best explained by an external incentive.